They Call It Filthadelphia:

How “Cash for Trash” Programs Abused Philadelphia’s Lower Class

By Juli Matlack

Introduction

According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, collecting recyclable material is the fifth most dangerous job in the United States, indicating that it is more dangerous than truck drivers (6th) but less dangerous than roofers (4th).[1] Recycling collectors and sorters perform laborious work. They lift, push, and pull heavy bins full of materials that have been collected over two weeks, if not more. The collection and sorting of materials requires strength and good body mechanics. You lift, bend, and twist, which holds serious risk for your body’s knees, shoulders, neck, and back. It’s all too easy to obtain painful injuries like pinched nerves and muscle strains just by doing your job to the best of your ability. Collecting recyclables in the dark or poor weather can leave you exposed to extreme temperatures and careless drivers. As if the labor wasn’t bad enough, working such a low status job can do a number on your psyche as well. Lack of respect, support, and job security are all part of the job most times and allows the stress of the work to burden your body as well as your mind.

In 1987, Philadelphia became the first major US city to implement a mandated recycling program. This program had many goals, the most important of which was to recycle 25% of the city’s waste by 1989, and 50% by 1991.[2] A program like this would not only benefit the environment, but if successful, it could help Philadelphia outgrow its unfortunate nickname of “Filthadelphia,” which stemmed from the city’s abundance of trash. A clean city would improve tourism, make those who live there happier with their environment, and of course help to save the planet. In short, the city’s reputation would benefit the most from cleaning up its streets. To better understand both the good intentions as well as the dangers of Philadelphia’s recycling program, see this 3 minute video essay I made for this project:

On paper the plan had no downside; it would benefit the environment, locals, tourism, and the city’s reputation. But there is a group missing from the list of beneficiaries: the lower class. The lower class would become the city’s “first line of defense regarding the program.”[3] The work done by the poor and working class is especially important for the program to run smoothly and efficiently, yet they are the least recognized groups and benefit the least. Monetary incentives were used by the city to encourage these classes to participate in the program, thus using these vulnerable classes as cheap labor.

But how did a plan intended to benefit Philadelphia as a whole turn into something that would disproportionately hurt the city’s poor and working class? Who was within the groups that were harmed by the implementation of the program, and how were they affected? What risks did recyclable material handlers face? We should also question what benefits came from the recycling program; does the chance of economic stability and job security outweigh the risks of bodily and mental harm?

To answer these questions, we have to analyze the program’s origins. From the very beginning, the program was flawed. It was rushed to launch without having completed logistical planning, which resulted in numerous challenges that caused city residents’ resistance to participate. To improve city participation, monetary incentives were offered to the city’s most vulnerable citizens, knowing that they would be unable to say no. The poor and the working class were targeted by the city to collect and sort recyclable material in exchange for a chance at economic stability, but their work put them and their health in danger. Ultimately, although the city of Philadelphia implemented its mandated recycling program with the intention of helping the city and its inhabitants, only members of the city’s upper-class community benefited from it, while the city’s poor and members of the working class were negatively impacted.

In this paper, I will analyze the city’s recycling program and how it hurt its most vulnerable citizens. We will first examine the city’s intentions to reveal that the interest in the program was likely not due to helping the citizens. I’ll next discuss the problems that the program faced from day one and on, and the solutions that Philly’s city officials put in place to correct the program. Finally, I’ll analyze the problems that arose from the “solutions” and clarify how they created additional problems for the poor, and why the city neglected further solutions due to who was being impacted. But in order to understand how the program hurt the economically unfortunate, first we need to understand what went wrong.

Philadelphia’s Recycling Program Proposal

Philadelphia city officials claimed to have the city’s best interests at heart when they passed a major recycling law in 1987, but their actions- or failure to act- speak louder than their words. The Philadelphia administration spent years talking about a recycling program before city council passed one in 1987.[4] It was agreed within the city government, particularly the Philadelphia Streets Department, that recycling needed to start in Philly at some point, though many suspect that the reason for it was to reduce trash disposal costs at landfills and incinerators.[5] Before the city council and Mayor Goode passed the 1987 recycling law, four consecutive mayors, including Goode, were pushing for a second incinerator as a way to combat the city’s abundance of trash.[6] Despite four mayors’ attempts, the city council continuously rejected the incinerator plans. Advocacy groups and environmentalists within the city were largely responsible for the council’s decision.

Advocacy groups played a large role in the program’s proposal; one group called Philadelphia for Recycling (PFR) was exceptionally present during the program’s proposal.[7] PFR argued that recycling benefits the city’s inhabitants by cleaning up the city and improving the standard of living as well as tourism. Other environmental advocacy groups cheered on the city’s program, though some of the council disagreed with the short timetable that was made.[8] They felt that the program’s implementation was being rushed, leaving too many logistical factors unplanned.[9] This rush to launch could be explained by remembering that if the program was successful, Philadelphia would be the first major city with a mandated recycling program, and this would no doubt improve the city’s reputation.[10

In order to strengthen their argument, PFR established a connection with City Council Representative David Cohen. Cohen developed plans to fight the Mayor’s incinerator plan. He argued for recycling with economic reasoning; a recycling plan would help the city save money by lessening trash disposal costs. With recycling, the city would pay less in incinerator or landfill fees as well as forestall the need to dispose of 100% of city trash. Between the advocacy groups and Cohen’s defense for recycling, the city council was pressured into passing the 1987 recycling law.

When the Philadelphia Street Department’s administration began hiring staff for recycling coordination, it became clear that the city’s higher administration was not committed to recycling. They paid little attention to the coordinator by only giving their staff the bare minimum of support.[11] An employee of the recycling team described the administration’s commitment as “pure lip service,” indicating that the city was developing a recycling program only for good public relations.[12] Their lack of commitment, rush to launch, and disinterest in anything other than a good reputation led to the program having efficiency and financial problems. It was clear within the Streets Department that despite council approval, Philadelphia government was not taking the benefits of recycling seriously and still wanted an incinerator.

In the program’s trial period, weekly curbside pickup began in a large middle-class neighborhood.[13] When the program yielded good results, the Streets Department began expanding to more neighborhoods of both the upper and lower class. However, after expansion into poorer neighborhoods it became clear that upper class neighborhoods were participating far more and that poorer neighborhoods had little interest nor time to participate.

Early Problems with the Program

Lack of proper logistical planning made the program’s implementation ineffective. In order for the program to function well, the city needed to improve its participation rates. In doing so, administration unwittingly targeted the city’s most vulnerable populations. The program proved to be logistically difficult to manage and financially unrewarding. In their rush to launch, the Streets Department neglected to consider the bulk of materials and the space available within garbage trucks. The department lacked proper equipment for city-wide curbside pickup.[14] Recycling trucks and garbage trucks are built based on the materials being collected in order to be more efficient. The city had only garbage trucks when the recycling program was implemented, causing inefficient collection. Bulky materials like plastic bottles as well as materials with little recycling worth were taking up too much space within the trucks. To improve collection efficiency, problem materials like these were removed from the approved material list.[15]

Budget cuts forced the city to cut the pickup schedule from weekly to biweekly. [16] Collection was expensive and the budget was unrefined prior to the program’s launch. In an attempt to make the program more cost-effective, trash and recycling collection was made less frequent, which also encouraged people to wait until their recycling bin was full before putting it on the curb.[17] Revisions of the schedule and accepted materials on top of having to adapt to separating trash from recyclables created confusion among the city’s participants, which damaged the already low participation rates.

Participation was a huge problem; affluent neighborhoods were carrying the weight of the poorer neighborhoods at 70-80% participation versus 20-30%.[18] Administration recognized that the inner-city neighborhoods, which were primarily low income, were resistant to participate due to a lack of connection with the administration. It should also be noted that the people in these neighborhoods were likely working more than one job, raising children, and had little time to worry about separating their trash or bringing it out for collection.

Still, these neighborhoods valued personability; they wanted face-to-face interactions before agreeing to changing their disposal habits.[19] A member of the Philadelphia Recycling Office (PRO) remembers “You can come around with buckets and circulars in the middle-class neighborhoods and get cooperation but the inner city is a different beast. People communicate over the stoop and wait for face-to-face contact before they participate in a program. I tried to let the people know that we were committed to helping them and that we weren’t just sending another suit into the community to promise great things.”[20] This shows that the recycling administration knew about a lack of trust the lower class already had towards city officials and proves that there was distrust towards the city’s “suits” and their promises about recycling. Still, there was low morale and resistance to the program. After the aforementioned revisions, participation dropped from 70-80% to 35%.[21] The city needed the poorer neighborhoods’ participation to improve in order to improve the program.

The Solutions

To get that participation, the city began “buying” the lower class’ participation. The city offered monetary incentives in poorer neighborhoods to employ the poor in collecting trash in exchange for cash, creating a mutual dependence between the city and the impoverished. There were two versions, one of which was a drop-off program in which a neighborhood would be paid to collect and bring their recyclables to a corner of their block for the city to pick up.[22] The payment would go back into the neighborhood in order to improve the community.[23] In this scenario, the entire neighborhood would benefit from the money, though they would all also have to collect, sort, and transport their own recyclables.

Drop-off programs were effective and cost efficient; they benefited the city because it offered employees Saturday hours, and it was far cheaper and easier than navigating each neighborhood for curbside collection.[24] It also benefited the neighborhoods by making recycling more convenient because they don’t have to transport it to recycling centers.[25] Also, the neighborhood benefited by the funds that were acquired based on the amount of materials recycled. Despite this program’s initial success, it was not applicable in all of the neighborhoods that needed a boost in participation. Instead, the recycling department developed a second incentive program.

The second program was a cash for trash program where individuals could collect materials throughout the city and bring them to a cash for trash facility in exchange for cash; each individual made their own money based on the materials they exchanged.[26] This program was most successful in the city’s poorest neighborhoods.[27] Philadelphia’s poor, many of which were homeless or without jobs, could use cash for trash programs as an opportunity for economic stability by supplementing the income of all who participate.[28]

However, this program came with additional risks because many neighborhoods had rules against where they could collect from, mostly banning collection of residential recyclables.[29] The city loses money when independent trash pickers collect from residential recyclables, making it difficult for pickers to find substantial materials worth anything.[30] It is important to note that with increased participation comes higher demand for workers within the city recycling centers. Collecting residential recyclables guarantees that these workers will have a job, and collecting materials independently and bringing them to a recycling center has the same result. Ultimately, pickers depend on non-residential streets, parking lots, and abandoned buildings, while the city is responsible for collecting residential and business trash; this dual-party system ensures that material collection covers most of the city.

These incentives seem beneficial, but they are problematic. By initiating them, the city created a mutual dependence between the PRO and the recycling collectors; the PRO needed the poor to increase participation rates, which would improve program efficiency and costs, and the poor as well as the working class needed the incentives in order to get by financially. The recycling collectors were “the city’s first line of defense in the city’s losing battle against skyrocketing trash disposal costs and shrinking landfill space.”[31] To clarify, they were an excellent form of cheap labor. Though the incentives did help the poor financially and guaranteed jobs for the working class, the pressure to work unfairly burdened the private collectors and city-employed workers with the health risks associated with this work.

Division of the Lower-Class

Two groups of the lower class were affected negatively by the city’s monetary incentives: the private collectors of the poorest communities and the city-employed workers of the working class. In order to understand the risks associated with their work, it’s important that we understand who these people were. In the 1980s, Philadelphia’s old and abandoned Nabisco factory was a recycling collector’s dream. Abandoned and bountiful with recyclable materials, scrap haulers frequented the property and filled their personal shopping carts with materials to trade for cash at local buy-back programs. Collectors would come with shopping carts and bags to hold their materials. The factory was eventually transitioned into a recycling center known as National Temple Recycling Center, where city-employed workers would sort recycling materials.

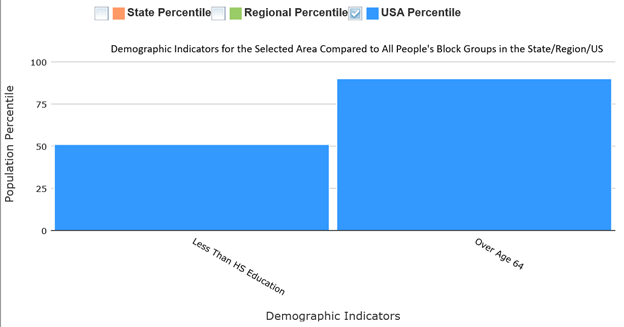

Using an environmental justice screening and mapping tool, EJSCREEN, I was able to study the demographics of people surrounding the old Nabisco factory. Within 0.25 miles from the old Nabisco factory, which was located in northeast Philly, 26% of the population was over the age of 64, as seen in the graph below. This is significantly higher than the average for the state or nation, putting this area in the 90th percentile in the USA. This suggests to us that the majority of recycling collectors who frequented the factory were elderly. This area also had many people with less than high school education. The value of people with this education is 10% and is actually pretty average for the state and the nation. However, having a population that is overwhelmingly elderly or undereducated allows researchers like myself to infer that there was probably little understanding of the environmental risks associated with the area. It also suggests that these people had little upward mobility. There were probably few job opportunities for these people, forcing them to rely on the factory as a garden for recyclable material to sell and later as an employment opportunity when the recycling center opened.[32]

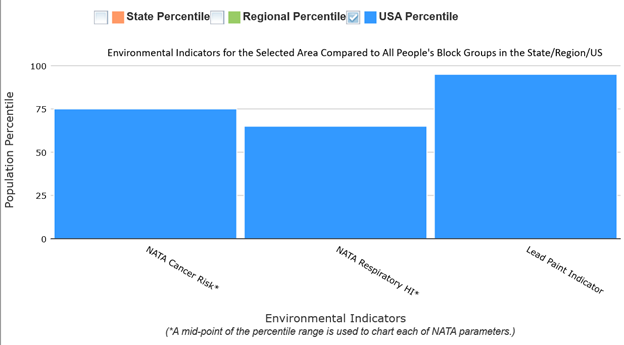

The old Nabisco factory was plagued with environmental indicators suggesting health risks for those who occupied or frequented the area. The lead paint indicator is outrageously high, as seen in the graph below. This indicator is a percentage of housing units that have possible exposure to lead paint due to being built before 1960; this is important to note because although the factory was not a residential building, having lead paint in surrounding houses makes it very likely that the old factory was also painted with lead paint. We know now that lead paint can have detrimental health effects. This property is in the 95th percentile for lead paint in the United States. The value of this data is 0.85; this is 3 times the national average of 0.28. This means that anyone who came into this area was very likely exposed to lead paint and we can be almost certain that the scrap haulers and recycling center employees who worked at the property were exposed as well. If you’re interested in more data from EJSCREEN regarding the demographics and environmental indicators within the area of the old Nabisco factory, you can find more of my data and analysis under the “Scientific Data Analysis” tab of this blog or by following this link: https://ejhistory.com/scientific-data-analysis-jm/.

Beyond the risks of the historic city’s buildings, recycling collectors were also exposed to more complex risks. A study on microbiological exposures from 2006 showed that handling waste puts people at risk for inhaling bioaerosols from bacteria and fungi that could negatively impact their health; this exposure is of “infectious, allergenic, and toxic hazards.”[33] The risk is raised when collection is less frequent, like Philadelphia’s biweekly collection system.[34] Also, the more trash there is, the higher the risk for exposure.[35] Both the independent collectors and the city’s employees risk exposure to these aerosols, although some may have better protection than others.

As I mentioned, the handling of waste and refuse is the 5th most dangerous job in the United States. This is because of the damage the job does to one’s body. Lifting heavy objects like full or overflowing recycling bins can lead to damage of the worker’s body. Lack of proper body mechanics, being overworked, and lacking mechanical equipment all put undue stress on workers’ bodies.[36] As a result of this grueling labor, recycling workers are at high risk for workplace-related musculoskeletal disorders, particularly of the neck, shoulders, and back.[37]

Not only are recycling collectors at risk for physical harm, but they are also exposed to psychological impacts. There is a stigma that comes from working with garbage, whether you are employed or not. There is a serious lack of respect for those who clean Philadelphia’s streets, leading to poor self-esteem among those who collect recyclables.[38] In an interview I conducted with a former Philadelphia resident Katie Tinklepaugh (pictured in the link below), she recalls private collectors “don’t want to be noticed or bother anybody. They just want to get what they need and go” and “they get pretty skittish when you look like you’re about to open your front door, so they would run away like they were thinking they were doing something wrong.”[39] It’s clear from this quote that private collectors felt self-conscious about their work, likely because of the negative stigma that damages their self-esteem. To hear more from Katie and her experiences with recycling in Philly, you can access the 17-minute interview below, or read the interview transcript here: https://ejhistory.com/oral-interview-or-storymap-jm/.

Again, you did not have to be unemployed to face this stigma; workplace conditions often wear down employees of recycling centers. There is a lack of respect and support not only from the community, but also from some workplace supervisors.[40] Higher participation in the program leads to higher pressure placed on the employees responsible for sorting materials quickly and efficiently; this pressure and lack of support can severely damage a person’s psyche, as seen in a pilot study on musculoskeletal disorders done by Thomas Fisher.[41] In David Pellow’s book Garbage Wars, he details the working conditions within recycling facilities in Chicago. Pellow has testimonies from employees describing the brutal conditions they work in; extreme heat or cold both within and outside of the building, intensive labor that is exacerbated by supervisors choosing not to use conveyor belts, and little independence or dignity at work.[42] Many of these conditions are shared with the private collectors, although again, the workplace often had better protections for workers.

The image below displays a man with a shopping cart carrying recyclable materials he has collected along his route to what we can assume to be a recycling facility that participates in a buy-back program that pays collectors cash for certain types and amounts of recyclable materials. The jacket that he wears look well-worn and thin, but the hoodie underneath and the beanie on his head indicate that it is cold out. He doesn’t wear gloves, which would benefit him in both cold weather as well as while he is picking through the trash. In our interview, Katie mentions remembering the clothing that she usually saw pickers wearing as “darker clothing so they don’t really stand out.”[43] This makes it risky for them to be out in either early morning or late night where cars may not see them very well. It’s clear that whatever money he makes through the buy-back program is going to things other than clothing for himself, and the thinness of his face causes me to believe that the money is probably going to his daily meals.

You can see in this image that the poorest citizens of Philadelphia live extremely different lives and experience extremely different conditions than the middle or upper-class. The scarcity of upward mobility resources in Philadelphia creates the dependence on buy-back programs, and this system is replicated throughout the country in post-war America: poor citizens are unable to attain or access the same resources as middle or upper-class and must rely on scraps leftover from these people as a way to survive. Despite performing what is essentially a very similar job, private collectors lack the same protections as city-employees.

In the image below, we see a line of workers sorting through a massive amount of materials on a conveyor belt. Each worker is donned with safety gear including hardhats, safety glasses, fluorescent vests, masks, and gloves. This suggests that there is probably formal training and uniforms required to attain this job, and that is probably paid for by the employer, aka the city. They appear to have far more protections than what the image of the private collector shows, and this is reinforced by Katie. She remembers “the people who pick up the trash, obviously they need to be in their hazardous clothes because they have cars and everything else going on around them.”[44] However, at the same time, we can see in this image that at least one worker is not wearing his mask correctly, putting him at risk for airborne dangers like the aforementioned bioaerosols. To better understand aspects of both of these images in relation to risks and protections, I provide further analysis in the “Image Analysis” tab of this blog at: https://ejhistory.com/image-analysis-jm/.

As Katie and Pellow both suggest, although images like this suggests safety measures were in place for employees, not all shared them. Katie recalls that the workers who collected her trash might not have even worn gloves, and definitely did not have any type of face mask.[45] Pellow’s book contains the testimony of a worker who recounts coworkers being struck by hypodermic needles, injured by battery acid, and working in areas with poor air quality.[46] Between the physical demands and risks associated with recycling and the psychosocial implications from testimonies, it becomes clear that Philadelphia’s poor and working class were targeted by the city’s monetary incentives because they were not in a position to refuse.

Conclusion

As I wote at the beginning of this essay, Philadelphia’s recycling program was intended to benefit the city as a whole. It is clear through my research, however, that not all of Philadelphia’s citizens benefited. As is the case in cities far and wide, the poor and working-class communities were disproportionately hurt by an administration with good intentions. Although the program benefited from increased participation and the incentives offered income supplements and partial job security for private and employed collectors alike, the damage that accompanies the job of recycling collection, handling, and sorting impacted the poor and working-class in ways that, frankly, are not worth the money offered. The chance for economic stability and upward mobility were too good to pass on, despite the risks that were seemingly unavoidable. Recycling was seen as this city’s, and the planet’s, savior. But who is saving the people working to save us in one of the most dangerous jobs in the nation?

Keyword Tags: class, business, toxics, pollution, recycling

[1] Beth Braverman. “The 10 Most Dangerous Jobs in America.” CNBC. December 28, 2019.

[2] Robin Clark. “Recycling Bill Passed by City Council.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. June 12, 1987. Pages 1A, 12A.

[3] “Philadelphia Recycling: ‘It’s a Living.’” The New York Times. August 9, 1987. Page 39.

[4] Robin Clark. “Recycling Bill Passed by City Council.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. June 12, 1987. Pages 1A, 12A.

[5] Robin Clark. “Recycling Bill Passed by City Council.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. June 12, 1987. Pages 1A, 12A.

[6] Susan Minter. “Linking Environmental Police with Economic Development: A Case Study in Urban Recycling.” Massachusetts Institute of Technology. June 1991. Page 76.

[7] Susan Minter. “Linking Environmental Police with Economic Development: A Case Study in Urban Recycling.” Massachusetts Institute of Technology. June 1991. Page 78.

[8] Robin Clark. “Recycling Bill Passed by City Council.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. June 12, 1987. Pages 1A, 12A.

[9] Robin Clark. “Recycling Bill Passed by City Council.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. June 12, 1987. Pages 1A, 12A.

[10] Robin Clark. “Recycling Bill Passed by City Council.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. June 12, 1987. Pages 1A, 12A.

[11] Susan Minter. “Linking Environmental Police with Economic Development: A Case Study in Urban Recycling.” Massachusetts Institute of Technology. June 1991. Page 78.

[12] Susan Minter. “Linking Environmental Police with Economic Development: A Case Study in Urban Recycling.” Massachusetts Institute of Technology. June 1991. Page 78.

[13] Jack Siderer and Mark Bersalona. “A Computer Evaluation of the Philadelphia Curbside Recycling Program.” Columbia University. 1988. Page 213.

[14] Mark Jaffe. “Recycling is off to a slow start.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. February 10, 1988. Pages 1B, 2B.

[15] Adrienne Redd. “Recycling on the Streets of Philadelphia.” World Wastes. Vol 37, Iss. 8. August 1994. Page 40.

[16] Mark Jaffe. “Recycling is off to a slow start.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. February 10, 1988. Pages 1B, 2B.

[17] Peter Grogan. “New Approaches to Lower Program Costs.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. July 1992. Page 35.

[18] Adrienne Redd. “Recycling on the Streets of Philadelphia.” World Wastes. Vol 37, Iss. 8. August 1994. Page 40.

[19] Adrienne Redd. “Recycling on the Streets of Philadelphia.” World Wastes. Vol 37, Iss. 8. August 1994. Page 40.

[20] Adrienne Redd. “Recycling on the Streets of Philadelphia.” World Wastes. Vol 37, Iss. 8. August 1994. Page 40.

[21] Adrienne Redd. “Recycling on the Streets of Philadelphia.” World Wastes. Vol 37, Iss. 8. August 1994. Page 40.

[22] Susan Minter. “Linking Environmental Police with Economic Development: A Case Study in Urban Recycling.” Massachusetts Institute of Technology. June 1991. Page 99.

[23] Susan Minter. “Linking Environmental Police with Economic Development: A Case Study in Urban Recycling.” Massachusetts Institute of Technology. June 1991. Page 99.

[24] Robert Steuteville. “Big City Recycling Moves Forward.” BioCycle. July 1993. Pages 30-34.

[25] Robert Steuteville. “Big City Recycling Moves Forward.” BioCycle. July 1993. Pages 30-34.

[26] United Nations University. Mega-City Growth and the Future. United Nations University Press. 1994. Pages 208-209.

[27] Susan Minter. “Linking Environmental Police with Economic Development: A Case Study in Urban Recycling.” Massachusetts Institute of Technology. June 1991. Page 49.

[28] United Nations University. Mega-City Growth and the Future. United Nations University Press.

1994. Pages 208-209.

[29] Megan Matuzak. “Trash Pickers in Fishtown: Where There’s a Will, There’s a Way.” The Spirit of the Riverwinds. May 20, 2015.

[30] Megan Matuzak. “Trash Pickers in Fishtown: Where There’s a Will, There’s a Way.” The Spirit of the Riverwinds. May 20, 2015.

[31] “Philadelphia Recycling: ‘It’s a Living.’” The New York Times. August 9, 1987. Page 39.

[32] United States Environmental Protection Agency. 2000 version. EJSCREEN. Retrieved: April 5, 2020.

[33] J. Lavoie, C. Dunkerley, T. Kosatsky, A. Defresne. “Exposure to Aerosolized Bacteria and Fungi Among Collectors of Commercial, Mixed Residential, Recyclable and Compostable Waste.” Science Direct. August 22, 2006. Page 24.

[34] J. Lavoie, C. Dunkerley, T. Kosatsky, A. Defresne. “Exposure to Aerosolized Bacteria and Fungi Among Collectors of Commercial, Mixed Residential, Recyclable and Compostable Waste.” Science Direct. August 22, 2006. Page 26.

[35] J. Lavoie, C. Dunkerley, T. Kosatsky, A. Defresne. “Exposure to Aerosolized Bacteria and Fungi Among Collectors of Commercial, Mixed Residential, Recyclable and Compostable Waste.” Science Direct. August 22, 2006. Page 24.

[36] Thomas Fisher. “Role of Occupational Therapy in Preventing Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders with Recycling Workers: A Pilot Study.” The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2017. Page 1.

[37] Thomas Fisher. “Role of Occupational Therapy in Preventing Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders with Recycling Workers: A Pilot Study.” The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2017. Page 1.

[38] Thomas Fisher. “Role of Occupational Therapy in Preventing Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders with Recycling Workers: A Pilot Study.” The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2017. Page 4.

[39] Katie Tinklepaugh (former Philadelphia resident) in discussion with the author, April 13, 2020. https://soundcloud.com/user-943153545/hist490-interview. 4min 43sec.

[40] Thomas Fisher. “Role of Occupational Therapy in Preventing Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders with Recycling Workers: A Pilot Study.” The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2017. Page 2.

[41] Thomas Fisher. “Role of Occupational Therapy in Preventing Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders with Recycling Workers: A Pilot Study.” The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2017. Page 1.

[42] David Pellow. Garbage Wars: The Struggle for Environmental Justice in Chicago. The MIT Press. 2002. Pages 119, 129, and 126 respectively.

[43] Katie Tinklepaugh (former Philadelphia resident) in discussion with the author, April 13, 2020. https://soundcloud.com/user-943153545/hist490-interview. 10min 35sec.

[44] Katie Tinklepaugh (former Philadelphia resident) in discussion with the author, April 13, 2020. https://soundcloud.com/user-943153545/hist490-interview. 10min 40sec.

[45] Katie Tinklepaugh (former Philadelphia resident) in discussion with the author, April 13, 2020. https://soundcloud.com/user-943153545/hist490-interview. 9min 22sec.

[46] David Pellow. Garbage Wars: The Struggle for Environmental Justice in Chicago. The MIT Press. 2002. Pages 153-54.